When asked to name the greatest soldier of the war, Robert E. Lee replied, “A man I have never seen, sir. His name is Forrest.” Nathan Bedford Forrest was certainly an extraordinary man, a Herculean hero of the American wilderness who has blotted his copybook amongst the politically correct because of allegations stemming from his capture of Fort Pillow and his part in the original Ku Klux Klan. But there is more to the story than that.

During the war, Nathan Bedford Forrest killed thirty men in hand-to-hand combat, had twenty-nine horses shot from beneath him, and proved himself a very “wizard of the saddle.” William Tecumseh Sherman said, “Forrest is the devil . . . .I will order them [two of his officers] to make up a force and go out to follow Forrest to the death, if it costs ten thousand lives and breaks the Treasury. There will never be peace in Tennessee until Forrest is dead!

To the Federals he might have been the “that devil Forrest,” as Sherman called him in a 6 November 1864 message to Grant, but to Confederates in Tennessee and Mississippi, he was a hero, the very embodiment of all the virtues of the Southern frontiersman: fearless, enterprising, honor-bound, unstoppable. Confederate General Richard Taylor (President Zachary Taylor’s son) said of Nathan Bedford Forrest that “I doubt if any commander since the days of lion-hearted Richard has killed as many enemies with his own hand as Forrest,” who was not only a strong-right arm in battle but an intuitive genius of a general.

Nathan Bedford Forrest: The Gunfighter

Forrest was born the son of a blacksmith in Bedford County, Tennessee. The family hunted and farmed for its food, and made their own clothes. Forrest had little formal schooling (less than a year, and his headmaster remembered him as being more interested in wrestling than reading). But he had plenty of good sense, worked hard for his family (especially after his father died), and killed varmints (including, like a young Hercules, beating a snake to death and hunting down a panther that had attacked his mother).

When it was rumored that Mexico would invade Texas, Nathan Bedford Forrest went off to fight. Unfortunately, there was no fighting to be had, so he worked his way back home, and set out to make his own fortune. That took him to Hernando, Mississippi, where an uncle had invited him to join his business, which included buying and selling horses and cattle.

On 10 March 1845, in a scene out of the oldWest, or the frontier South, four men—a planter named Matlock, two Matlock brothers, and an overseer— came to settle a dispute with Forrest’s uncle. Forrest saw their ill intent and intervened. He had no interest in the quarrel, he told them, except to even the odds: four against one wasn’t fair. One of the brothers drew on Forrest, missing him, but his uncle was struck and killed. Bedford fired back with his two-shot pocket pistol, each shot striking one of the Matlocks, leaving them wounded in the mud. Out of ammunition, he accepted a Barlow knife from a bystander, slashed the last Matlock into submission, and watched the overseer flee.

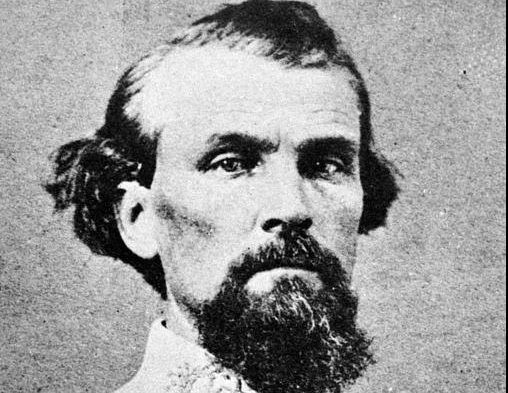

Though wounded himself by a pistol ball, Nathan Bedford Forrest was no easy man to take down. Six-foot-two, broad-shouldered, muscular, his dark wavy hair combed back from his unwavering iridescent blue eyes, he was, as John Allan Wyeth, who rode with him, remembered, “born a leader of men, not a follower of man.”

In that, too, he was a Southerner, for civilization in the old South was based on honor; and honor meant that Nathan Bedford Forrest was punctilious about dressing immaculately, about treating women with deference, and making sure that folks minded their manners (or paid the price). It meant that he worked hard, aiming not only to make money, but to earn a reputation as a respectable man. When he became a millionaire (largely through slave-trading), it was as a means to become a landed gentleman and leader—not to pursue the life of a sybarite.

He was soft spoken, except when angry. Then his face would flare and his tone would menace. He had a furious, animal temper, and could swear a blue-streak, but abhorred obscene language and never used it himself. Nor would he tolerate dirty stories. He didn’t drink, saying “My staff does all my drinking,” and didn’t smoke. His amusements were horse-racing and gambling. He refused to tolerate disorder, to the point where if his headquarters wasn’t swept he’d do it himself. When it came to romance, he was a buckskin knight. He might not have read Ivanhoe, the most influential book in the Old South after the Bible, but chivalry was ingrained in him.

Nathan Bedford Forrest met the woman who would be his wife when she and her mother were in a wagon stuck in a mud hole. Bedford rode up and rescued the women, carrying them across the mud, and then pushing the wheel free. Two men on horseback sat by watching. Bedford, in the words of Andrew Nelson Lytle, “told them they were ungallant and unfit to be in the presence of ladies, that if they didn’t ride away immediately, he would give them the worst whipping of their lives.” They took his word for it and skedaddled. After returning the ladies to their wagon, he asked permission to call on the younger, Miss Mary Montgomery. Permission granted, he turned up the next day, found the same two ungallants in the parlor, scattered them like hares, and told Miss Mary he wanted to marry her. Her father Cowan Montgomery, a Presbyterian minister, disapproved. “Why, Bedford, I couldn’t consent. You cuss and gamble and Mary is a Christian girl.” Forrest replied, “I know it, and that’s just why I want her.” In a battle of wills, Forrest was not the sort who would ever relent; Cowan did.

The Slave Trader

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s growing business interests led him to Memphis and slavetrading, at which he grew so adept that he became one of the leading slave dealers of the Middle South. To read about the slave trade of the1850s is to enter a world where brokers advertise that they have “constantly at hand the best selected assortment of Field Hands, House Servants & Mechanics, at their Negro Mart.” The firm welcomes customers to “examine their stock before purchasing elsewhere” and volunteers to sell slaves on commission, promising that they will always acquire “the highest market price . . . for good stock.”

It sounds a bit like something out of the casbah. But it should also remind us of something else: slavery was an accepted commercial transaction in the South. One inspected a prospective slave the way one inspected a horse one was hankering on buying (or perhaps today a car).The slave dealer—or the slave’s previous owner—had a large financial stake in ensuring that the slave was strong, healthy, and unmarked by a whip or beating. Slaves were expensive, and a slave who bores cars not only reflected badly on the previous owner (the way a mistreated horse might) but was no more attractive to purchase than a car full of dings and dents and whose warning lights flash on the dashboard: either the slave was of bad character or the owner was—and planters prided themselves on their honor as much as any Southerner did.

As an aspiring planter, Nathan Bedford Forrest strove to be an impeccably honest and well-meaning slave trader. There is, of course, no getting around the fact that he was buying and selling human beings, and working to make a profit. But within that sadly confined moral circle, he acted as well as he could. According to his biographer Andrew Nelson Lytle, “He never separated a family, and he always did his best to find and buy the husband and wife, when either one was missing. He treated his slaves so well that he was burdened with appeals from them to be bought [by him].”

If cynics doubt the honesty of this portrayal, they should read Nathan Bedford Forrest’s advertisements, which take a similarly paternalistic line, promising that “cleanliness, neatness and comfort” were “strictly observed and enforced” in his slave mart. Moreover, “Persons wishing to dispose of a servant may rest assured that, if left with us, a good home will be secured.” It was this paternalism that allowed Southerners to tell themselves that while heartless Yankee capitalists treated their workers with callous inhumanity, Southerners treated their black “property” as real people, people to be clothed, fed, housed, and found “a good home,” and that could never be cast away into the streets.

By the time of Lincoln’s election, Nathan Bedford Forrest’s business interests—from real estate to his slave mart—had made him a millionaire. He was now what he had aspired to be, a planter and a respected member of the community. Since the day he had faced down the Matlock brothers, he had always been marked as a leader. In Hernando, Mississippi, he was a constable, in Memphis an alderman. In every position of authority he held, he was rigorously honest, and an enemy of corruption and cowardice. In one incident in Memphis, he single-handedly rescued a man from a lynch mob’s noose, fighting through the crowd to put the untried man in jail. When the mob surged around the jail threatening to break in, Forrest strode out, a six shooter in each hand, a big knife tucked visibly in his belt, and said matter of factly: “If you come by ones, or by tens, or by hundreds, I’ll kill any man who tries to get in this jail.” That put paid to the mob’s ardor.

When war came, Nathan Bedford Forrest, as a wealthy man, had much to lose and opposed secession. He, like most men in the upper South and many in the lower South, hoped for a regional compromise. But it is characteristic of the man that when Tennessee seceded, he followed his native state and enlisted as a private (as did his youngest brother and fifteen-year-old son) in Captain Josiah White’s Tennessee Mounted Rifles.

Confederate Cavalryman

But Nathan Bedford Forrest was not long for the enlisted ranks. Local notables petitioned the governor and soon Forrest was a lieutenant colonel charged with raising his own regiment of mounted rangers. Troopers were asked to bring their own horses, equipment, and arms (shotguns and pistols preferred), but for those without he bought 500 Colt navy pistols, 100 saddles, and other cavalry impedimenta, which he cleverly smuggled (along with recruits) out of officially neutral Kentucky and past the noses Federal forces.

His first major engagement was at Sacramento, Kentucky. His men, riding through the town of Rumsey on the way to Sacramento, were cheered by the Kentucky belles who urged the men forward. Among them, according to Forrest’s report, was “a beautiful young lady, smiling, with untied tresses floating in the breeze, on horseback, [who] met the column just before our advance guard came up with the rear of the enemy, infusing nerve into my arm and kindling knightly chivalry within my heart.” More than kindling knightly chivalry within his heart, she told Forrest what she knew of the Federal dispositions at Sacramento.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s men raced to the attack of the enemy, engaging first in skirmish fire, and then, with flankers on the left and right, a head-on charge that broke the Federals, sending them reeling through the town. One trooper reported that at the outset of the battle, “there were at least fifty shots fired” at Forrest “in five minutes” and that Forrest, in turn, must have “killed 9 of the enemy.” Forrest led the charge after the retreating Federals, and fighting with pistol and saber brought down at least two more Federals and disabled another officer in blue who became his prisoner.

In action, he was a berserker, or in the words of Major David C. Kelley, this was “the first time I had seen the Colonel in the face of the enemy, and, when he rode up to me in the thick of the action, I could scarcely believe him to be the man I had known for several months.” Forrest’s face was flushed red so that “it bore a striking resemblance to a painted Indian warrior’s, and his eyes, usually mild in their expression, were blazing with the intense glare of a panther’s springing upon its prey. In fact, he looked as little like the Forrest of our mess-table as the storm of December resembles the quiet of June.”

“I am going out of this place or bust hell wide open”

His troopers’ next assignment was at Fort Donelson where Nathan Bedford Forrest immediately distinguished himself by picking off a Federal sniper. But the bigger problem was the tightening Federal grip around the besieged fort, which fronted the Cumberland River. The first plan agreed to by Confederate generals Gideon Pillow, John B. Floyd, and Simon B. Buckner was to force a passage through the Union right. In fierce fighting, in which two horses were killed beneath him, one by an artillery shell, Forrest and his men blazed a trail that would have allowed the Confederate army to escape to Nashville, but General Pillow recalled the Confederates to their original lines.

That night the generals resolved to surrender the fort. Nathan Bedford Forrest, disgusted, told the generals that the men had a lot more fight left in them and won their permission to bring out his own command if he could. Forrest told his men, “Boys, these people are talking about surrendering, and I am going out of this place or bust hell wide open.” He told one soldier who decided to remain behind with his comrades, “All right; I admire your loyalty, but damn your judgment!”16 Most of his command shared his judgment and rode out into the frosty night, and into freedom, on 16 February 1862.

Nathan Bedford Forrest and his men saw duty at Shiloh, where Forrest was disconcerted to hear that his son had gone missing, only to find the fifteen-year old trooper shepherding Union prisoners. When Beauregard decided to retreat, Forrest was assigned to the rear guard, where he battled William Tecumseh Sherman at Fallen Timbers. In an engagement of typical Bedfordian fury, the fiery Tennessean charged the Federals, broke through their ranks—and suddenly found himself cut off and surrounded by bluecoats yelling “Kill him! Kill him!” One of the Federals planted a rifle barrel in his side and pulled the trigger, shooting a ball of lead near Forrest’s spine. But Forrest merely grimaced, hurled a bluecoat up behind him as a shield, and spurred and shot his way through the Federals, dropping the bullet-ridden Yankee once he was safe. Forrest’s right leg was numb, and the doctors, probing bloodily, couldn’t find the ball in the small of his back.

He was given two month’s leave to recover. He only allowed himself three weeks, and spent that time advertising for new recruits with this winning tagline: “Come on, boys, if you want a heap of fun and to kill some Yankees.”17 As it was, Forrest took command of a new unit of cavalry made up of Georgians and Texans, which he led on raids into Tennessee, where they learned his tactics of charge—“Mix with ’em, boys!”—and bluff.

After shocking a Federal position by his sudden appearance or with a brief, bold attack, he would demand its unconditional surrender. Failing that, he threatened, he could not be held accountable for the consequences, given that his men’s blood was up. While the Federals considered his demand, Forrest would make a show of his riders and artillery—the same riders and artillery repeatedly pulling in and trotting out, but fooling the Federals into thinking they were ever expanding numbers of grey cavalrymen and rebel cannon.

He performed this theme of fierce charges and gambler’s bluff with variations throughout the entire war, and it was crucial to his success because his troops were usually ill equipped. To gain an adequate supply of guns and ammunition his men had to take them from the Federals. Surrendering Federal officers became the inadvertent quartermasters of Forrest’s “critter company.”

“Ah, Colonel, all is fair in love and war”

Though an accomplished raider, Nathan Bedford Forrest was also a brigadier general (as of late July 1862). But Confederate General Braxton Bragg tended to think that raiding and recruiting were Forrest’s forte, and so rather than incorporate him into a regular body of cavalry, Bragg repeatedly chose to take Forrest’s troopers for the army, and send Forrest out to raise more men and engage in more raids. Forrest didn’t mind the call to action, but he did come to resent Bragg’s limitation of his role.

That Nathan Bedford Forrest was aggressive cannot be doubted, but he was also a realist and advocated against an attack on the Federal position at Dover, near Fort Donelson, in February 1863, though he was ordered to do so by General Joseph Wheeler, a Georgia-born West Pointer and cavalry officer. The attack itself was a failure—in part because of Forrest’s aggression leading him to charge the Federals when he thought they were retreating; they weren’t. Forrest’s horse, as was common, was blown from beneath his legs, though Forrest, as ever, survived. His temper, however, didn’t. After the battle he told Wheeler, “I mean no disrespect to you; you know my feelings of personal friendship for you; you can have my sword if you demand it; but there is one thing I do want you to put into your report to General Bragg—tell him that I will be in my coffin before I will fight again under your command.” Wheeler reassured him of his esteem, the moment passed, and Forrest would serve under Wheeler again.

In April 1863, Nathan Bedford Forrest’s men, usually the chased (after their raids), became the chasers, pursuing a unit of Federal raiders under the command of Colonel Abel D. Streight who charged across northern Alabama. Forrest kept his men at Streight’s heels, but at one point it looked like the Federal colonel had bested Forrest, escaping over Black Creek and burning the bridge behind them. As at Sacramento, however, help came from the fairer sex. A young girl at a nearby farmhouse called out to Forrest and told him she knew another crossing. He pulled her up behind him on the saddle (reassuring her mother that he’d bring her back safe) and had her guide him to the ford, where his men crossed to continue their harassment of the Federals. Forrest left the girl (named Emma Sansom) a note—an official commendation of her service.

When Nathan Bedford Forrest finally called upon the Federal commander to surrender his exhausted troops, his men employed the old Forrest bluff strategy, moving around artillery pieces until Streight said: “Name of God! How many guns have you got? There’s fifteen I’ve counted already!” Forrest replied, “I reckon that’s all that has kept up.” After a little more bluff and threat, Streight tossed in his hand—1,466 blue-coated soldiers. When he saw that Forrest had only 400 to 600 men, he protested, to Forrest’s laughing rebuke: “Ah, Colonel, all is fair in love and war.”

He was less fortunate in a misunderstanding with one of his own officers, Lieutenant A. W. Gould, whom Forrest had rashly and wrongly accused of cowardice, and ordered transferred to another unit. Gould met with Forrest at the Masonic hall (commandeered by the quartermaster) in Columbia, Tennessee, to personally protest the order. Forrest took it personally, too. When Forrest refused to reconsider, Gould allegedly pulled a gun on Forrest. The gun misfired, wounding Forrest, who struck back with a pen knife (which he used as folks today use dental floss), slamming it into Gould’s ribs while he simultaneously deflected Gould’s gun hand upwards.

Gould fled and was taken in by two doctors who tried to stanch the bleeding; Forrest was assisted by another doctor who told him that the gunshot in his side might be fatal. Forrest pushed him aside and stumbled out into the street swearing “No damned man shall kill me and live.” One man tried to stop him, saying Gould was mortally wounded. That didn’t matter. Having picked up a revolver, Forrest burst in on Gould and his doctors. Gould had life enough still in him, to make a break for it, running down an alley before collapsing in a pile of weeds. Forrest strode over to him, rolled him over with his boot, and, seemingly satisfied, stalked off.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s wound was, miraculously, not fatal as the ball hit no vital organs. Gould was not so lucky, and now that the mortal balances had shifted in Forrest’s favor, Forrest was filled with remorse. He told his doctors to go away, “It’s nothing but a damn little pistol ball; leave it alone!” And he demanded that Gould be given every consideration of treatment, which Forrest would pay for. Gould died, but not before he and Forrest were reconciled, according to some accounts.

Nathan Bedford Forrest versus Bragg

Within a fortnight Forrest was back in action, covering the retreat of Bragg’s army and being barracked by a woman as he sped through her town: “You great big cowardly rascal; why don’t you fight like a man, instead of running like a cur? I wish old Forrest was here. He’d make you fight.”

Nathan Bedford Forrest fought again, and was wounded again, at Chickamauga, with another ball lodged near his spine. But while he broke his rule of abstention and accepted a swig of whiskey for the pain, he stayed in action at the battle—indeed he stayed in the battle more than the commanding general Braxton Bragg did. With the Federals in retreat, Forrest sent a dispatch through General Leonidas Polk for Bragg, laying out what he saw of the Federal evacuation and offering the admonition, “I think we ought to press forward as rapidly as possible.” He followed this up with another dispatch, urging haste because “every hour is worth 10,000 men.” His reports were seconded by a Confederate soldier who had escaped the Federals and was sent to Bragg to relay information on the Union retreat. The skeptical Bragg asked the trooper if he knew what a retreat looked like. “I ought to General, I’ve been with you during your entire campaign.” Forrest likewise grumbled about Bragg: “What does he fight battles for?”

Bragg’s advance on the Federals was not only, in Nathan Bedford Forrest’s view, lackluster at best, but he redoubled the crime by sending an order to Forrest— now fighting off Union cavalry—that his command was being transferred to Wheeler. This set the stage for the greatest verbal showdown of Forrest’s career. He spurred into Bragg’s camp, burst into his tent, and let fly with a speech of damnation that ended with these words:

I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to. You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your face jaws and force you to resent it.

You may as well not issue any more orders to me, for I will not obey them. And as I hold you personally responsible for any further indignities you try to inflict on me.

You have threatened to arrest me for not obeying your orders promptly. I dare you to do it, and I say to you that if you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path, it will be at the peril of your life.

Bragg decided to grant Nathan Bedford Forrest a transfer.

Controversy at Fort Pillow

In early 1864, Nathan Bedford Forrest’s youngest brother was killed in action—and Forrest, to avenge his death, personally charged the enemy in such fierce hand-to-hand fighting that his own men thought he was engaged in suicidal combat. By March 1864, Forrest was seeking to avenge more than his brother, he was seeking redress for outrages against pro-Confederate Tennesseans at the hands of Union troops or pro-Union militia. The alleged crimes included murder (one such being an officer of Forrest’s command who was captured while looking for deserters, and then, allegedly, tortured, killed, and mutilated), detention without charge, and extortion (bilking Southern townsmen out of thousands of dollars to spare their towns being burnt). Nathan Bedford Forrest sent a note of protest to the Union commander at Memphis and a dispatch to Confederate General Leonidas Polk. But he also prepared for action. In April 1864 he fought the most controversial battle of his career, at Fort Pillow, Tennessee.

Nathan Bedford Forrest hoped to capture the fort in order to supply his men; he did not expect much resistance. The Federal force defending the fort was made up of black troops (mostly freed slaves) and pro-Union Tennesseans. Forrest thought little of them as soldiers, and thought of the latter as traitors and the sort of renegades who abused their pro-Confederate neighbors. His approach against the fort was well-conducted, seizing forward buildings and surrounding the fort which, however, backed onto the Mississippi River, where the Federals had a gunboat.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s men outnumbered the Fort’s defenders (not including the gunboat) by about three to one. As per his usual procedure, he tried to convince the bluecoats to surrender and threatened that if they did not he could not be responsible for the fate of the Federal command. But the Yankees refused—apparently doubting that they were really dealing with the fearsome Forrest—and the defenders behind their parapet even goaded the attackers to come and get them. Forrest was willing to oblige. Nathan Bedford Forrest set his Missourians, Mississippians, and Tennesseans the contest of seeing who could breech the Federal lines first. Forrest, uncharacteristically, did not lead the charge himself. He had already had one horse shot beneath him that day (two more would follow) and it appears he might have been a nursing a sore hip.

The Confederates swarmed through the fort’s outer defenses (a ditch and parapet followed by earthworks) and then charged into the fort. The resulting melee, with Confederates firing into the Federals at point-blank range degenerated into a massacre as bluecoats fled to the river in vain hope of joining the gunboat, which Confederate fire kept driven back. In the frenzy and chaos of the blood-dimmed tide, bluecoats threw down their guns and were cut down after them. Men attempting to surrender were shown no quarter. But what happened was no organized atrocity, though Federal propaganda later tried to make it so, especially playing the race card, accusing the Confederates of murdering the black troops who suffered disproportionate casualties. (Fifty-eight of the 262 black defenders were made prisoners, as were 168 of the 295 whites.)

But any disinterested view of the battle and sober assessment of the evidence leads one to an opposite conclusion. Though he had no love for “Damn Nigger Regiments” and “Damn Tennessee Yankees,” Forrest and his officers tried to rein in their men as quickly as they could, once they realized that what had started as a battle had degenerated into a rampage.26 That Nathan Bedford Forrest had hoped to take the fort without bloodshed was obvious from his demand for its surrender. That men on the sharp-end (rather than the propaganda end) of battle understood the Fort Pillow “massacre” for what it was can be demonstrated by the fact that Sherman, who investigated the incident, declined to seek retaliation, though he had been authorized to do so by Grant, if the facts justified it.

Fighting to the end

On 10 June 1864, Nathan Bedford Forrest fought his greatest independent pitched battle, ambushing Federal forces under Union General Samuel D. Sturgis at the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads, and sending Sturgis’s much larger force— 8,500 Federals to 3,500 Confederates—in harried retreat, with Sturgis pleading, “For God’s sake, if Mr. Forrest will let me alone, I will let him alone.” Forrest not only defeated the Federals but relieved them of 16 pieces of artillery, 176 wagons, and a huge amount of ammunition and arms. Sherman was appalled at Sturgis’s defeat but noted that “Forrest is the devil, and I think he has got some of our troops under cower. . . . I will order them [two Federal officers] to make up a force and go out to follow Forrest to the death, if it costs ten thousand lives and breaks the Treasury. There will never be peace in Tennessee until Forrest is dead!”

Unfortunately for the Confederacy, Nathan Bedford Forrest was not sent to harry Sherman’s rear in Tennessee and Georgia; he was kept in the sideshow war of Mississippi, where he remained audacious even as his years of hard campaigning were starting to take their toll on his health. He was shot again, this time in the foot, at the Battle of Harrisburg, near Tupelo, Mississippi— a bloody repulse for the Confederates, and one that shattered Forrest’s command, but not badly enough for Sherman’s liking, because despite rumors to the contrary, Forrest survived. His presence, riding back from the hospital, reinvigorated the Confederate cavalry.

Indeed, this seemed to be Nathan Bedford Forrest’s role in the last year of the war: to reinvigorate Confederate morale with daring raids, such as he made into Memphis in August 1864, while the country’s borders withered under the torches of the advancing Federals. General Richard Taylor more or less gave him this duty, telling Forrest to do what he would, and report only to him. Forrest, operating now in Alabama, captured the Federal garrison

(1,900 men) at Athens in September 1864, destroyed the heavily guarded trestle at Sulphur Springs, and caused such trouble that Sherman had 30,000 men converging on the Confederate commander to “press Nathan Bedford Forrest to death.” But Sherman confessed that Forrest’s “cavalry will cover one hundred miles in less time than ours will ten.”

Nathan Bedford Forrest followed up his Alabama-Tennessee raids with a long-held plan to harass the Federals’ river-borne supplies. His men captured Federal supply boats and turned them into impromptu gunboats for Forrest’s new-styled “Hoss Marines.” They shelled Federal transports on the river and obliterated supply dumps. At Johnsonville, Tennessee, on the Tennessee River, they inflicted millions of dollars worth of damage on Federal stores on 3 November 1864. He did this, while Federal intelligence reports had him roaming about up North, in disguise, preparing, according to a Union provost-marshal, to “seize telegraph and rail at Chicago, release prisoners there, arm them, sack the city, shoot down all Federal soldiers, and urge concert of action with Southern sympathizers.” Forrest had no plans of fomenting an insurrection in Chicago. His plans were closer to home, as he wistfully remarked to his artillery officer John Morton,“ John, if they’d give you enough guns and me enough men, we could whip old Sherman off the face of the earth!”

Instead, Nathan Bedford Forrest was recalled to join in the bloody futility of John Bell Hood’s invasion of Tennessee in which the Confederate army of the West smashed itself to pieces, and then retreated, covered by Forrest, through bloodied ice and snow. Nathan Bedford Forrest finished the war as a lieutenant general, and to the end, he continued to fight the enemy hand-to-hand. In battle at Bogler’s Creek, he was attacked and pursued by Federal cavalrymen whom he held off and parried with his revolver, while battered by saber blows.

When it came time to surrender, he declined thoughts to lead his men to Mexico (though he entertained the idea later, after the war, as a possible mercenary adventure) or to go farther west and continue the struggle. He knew the game was up, though defeat was as bitter for him as for any who wore the rebel grey. In early May 1865, about a month after Lee’s surrender, he told a die-hard politician, “Any man who is in favor of a further prosecution of this war is a fit subject for a lunatic asylum, and ought to be sent there immediately.”

He also did something that his detractors might not expect. Before the war was over, he freed his slaves. In later congressional testimony, Nathan Bedford Forrest said that at the beginning of the war he called his slaves together and told them that if they stuck with him to the end of the war, he would set them free. He was as good as his word.

Reconstruction’s foe

By his own confession, the war had “pretty well wrecked him.” He felt “completely used up—shot to pieces, crippled up.” His finances were equally shattered. He relinquished some of his land, which he could no longer afford, and set about trying to farm some of the rest and return his saw mill to operation. He employed newly free blacks—at higher than standard wages, according to the Freedman’s Bureau—and brought into partnership several Union officers. The gentlemen in blue got a rude welcome when the general’s surviving war horse, King Philip, always enraged at the sight of blue uniforms, tried to attack them. One of the Union officers remarked it was no wonder that Nathan Bedford Forrest had built up a reputation as the very devil of a general, “Your negroes fight for you, and your horses fight for you.”

Still, Nathan Bedford Forrest faced the prospect of being tried for treason (he was indicted but never brought to trial) and for murder. The murder trial did happen, and Forrest was found innocent on the grounds of self-defense. He had intervened when he heard a black field hand named Thomas Edwards assaulting his wife. Edwards was notorious as a wife beater and for having a foul temper. Forrest burst into Edwards’s cabin and told him his days as a wife-beater were over. Edwards swore and said that no one would stop him from thrashing his wife. Edwards grasped a knife. Forrest whacked him with a broom handle—and when that only incited Edwards to attack, the general reached for an axe and struck Edwards dead.

According to one Union officer working for the Freedman’s Bureau, Nathan Bedford Forrest exhibited a dangerous leniency with his freedmen that encouraged affairs like that of Thomas Edwards. It was one thing, and a just thing, to treat the freedmen well—which he said, Forrest did to an unparalleled degree—but it was quite another to make liberal loans to the freedmen and allow them to buy and carry arms. And indeed, while Forrest waited for the authorities to arrive after his fight with Edwards, a group of armed freedmen had apparently surrounded Forrest’s house, though no further incidents of violence occurred.

Violence, however, was endemic in the tensions of Reconstruction, with disgruntled Confederate soldiers feeling stripped of their rights, freedmen heady with their new freedom, and Federal troops sitting in occupation on the South, executing the laws passed by the Radical Republicans who controlled the U. S. Congress.

Nathan Bedford Forrest tried to live by the advice he had given his troops—to obey the law. He applied for a pardon from President Johnson, and put his energies to work at a variety of business interests hoping one of them would bring his family financial security. He also apparently joined the newly formed Ku Klux Klan to, in his own mind, return order to the South.

The Klansman

What Nathan Bedford Forrest did within the Klan is ambiguous if for no other reason than that he denied having been a member of it or having anything more than a general knowledge of it, though he is often considered to have been elected its first commander in chief, or “GrandWizard.” By his own testimony he was not a member, but was “in sympathy” with the Klan and would have cooperated with them in a stand-off against Reconstruction radicals.

Nathan Bedford Forrest openly thought of the Klan as a defender of Southern rights against the depredations of the Radical Republicans. He publicly discounted reports of its crimes as mostly untrue. He believed that it was led by former Confederate officers who were honorable and disciplined, whose purpose was not the spread of anarchy or insurgency, but the preservation of order and peace. If Longstreet believed in accommodating the new order by being a Republican, Forrest, characteristically, called for peace and obedience, unless the Radical Republican authorities were to press things too far. If, Forrest told a reporter, the governor of Tennessee ordered out the militia against the people of the state and committed “outrages,” it would be the equivalent of a declaration of war; and if the governor declared war against the people of Tennessee, he would fight against him. It is in this light that Forrest viewed the Ku Klux Klan.

The view that the Radical Republicans did not have the interests of the South, or the Constitution, at heart, was widespread among former Confederates. The Radical Republicans, they believed, were using their power in Congress to grind the faces of former Confederates in the mud, denying them their political and civil rights and setting up newly freed blacks as chattel voters to enforce the Republicans’ will. So sober a figure as

Robert E. Lee, who like Nathan Bedford Forrest had made the case for submission and obedience, told a U.S. senator: “a policy which will continue the prostration of one-half the country, [and] alienate the affections of its inhabitants from the Government . . .appears to me so manifestly injudicious that I do not see how those responsible can tolerate it.” Tolerating insults was not Forrest’ strong suit.

Nathan Bedford Forrest said that he would defend the people of Tennessee against any radical depredations, but he wanted to make it clear: “I have no powder to burn killing negroes. I intend to kill the radicals [Radical Republicans]….I have told them that they were trying to create a disturbance and then slip out and leave the consequences to fall upon the negro; but they can’t do it.”

In Nathan Bedford Forrest’s mind and public professions, the Klan was not an antiblack organization—except in its origins, which were, it was said, to defend white women and children from hungry, armed, newly freed blacks looking for food on Southern farms—it was an anti-Radical Republican organization. Though the Klan was notorious for plying its trading of frightening, intimidating, and threatening freedmen, when not whipping and lynching them, Forrest maintained that such terrorism was not its purpose. It was organized to protect Southerners from pro-Reconstruction groups who were “killing and murdering our people.” He confessed, “There were some foolish young men who put masks on their faces and rode over the countryside frightening negroes; but orders have been issued to stop that, and it has ceased.”

Whether or not Nathan Bedford Forrest led the Ku Klux Klan, its “General Order” dated 17 July 1867, said much the same: “We are not the enemy of the blacks, as long as they behave themselves, make no threats upon us, and do not attack or interfere with us.” It also denied that the Klan had authorized any of the acts of unprovoked violence that had been carried out in its name; and in fact repudiated these as “wrong! wrong! wrong!” The Klan, it pronounced, “is prohibited from doing these things, and they are requested to prohibit others from doing them, and to protect all good, peaceful, well disposed and law abiding men, whether white or black.” When the Klan could no longer be controlled as a force for order, or according to some views, once Forrest thought he could no longer control it, it was dissolved as a unified organization in 1869. Forrest himself testified that he had helped dismantle it. And it is certainly true that he was later a public opponent of white vigilantism and a proponent of racial amity.

Nathan Bedford Forrest actually wanted more blacks to come to the South (in one cockamamie scheme, he thought perhaps the United States could ransom the prisoners of African chiefs and bring them to the South as free laborers). He also testified on behalf of importing Chinese coolies. When it was protested that black laborers would disapprove, he countered that the railroad project he was promoting had support both in financial subscriptions and in a stockholders’ vote among black Southerners (and he had the numbers to prove it).

Nathan Bedford Forrest died in 1877. Only two years before he had declared himself a Christian and became a member of the Presbyterian church. He had always supported Christianity in principle and shown an interest in it and believed in its moral teachings, but it was only at the end of his life, when he was pretty well used up, that the gambler locked up his cards and the man of violent temper and words tried to keep both shackled. He confessed he felt the better for it, and as he said, “I have seen too much of violence, and I want to close my days at peace with all the world, as I am now at peace with my Maker.” And so he did.

Cite This Article

"Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest: (1821-1877)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 13, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/confederate-general-nathan-bedford-forrest-1821-1877>

More Citation Information.