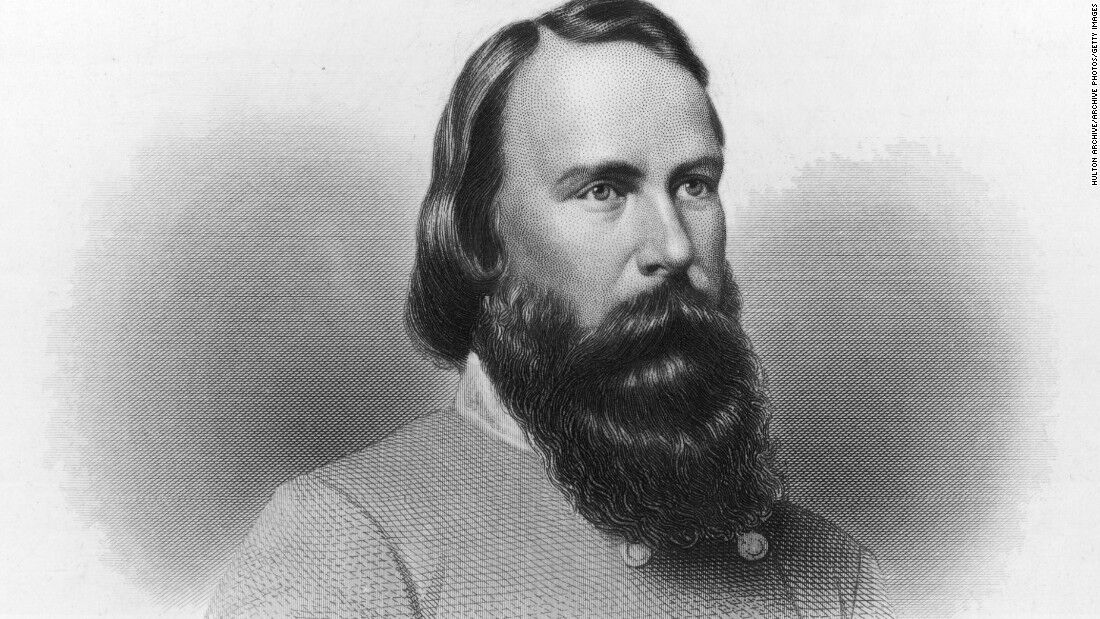

At the beginning of the war a cavalry officer, Moxley Sorrel, joined the staff of Brigadier General James Longstreet. Sorrel described Longstreet as “a most striking figure, about forty years of age, as oldier every inch, and very handsome, tall and well proportioned, strong and active, a superb horseman and with an unsurpassed soldierly bearing, his features and expression fairly matched; a full brown beard, head well shaped and poised. The worst feature was the mouth, rather coarse; it was partly hidden, however, by his ample beard.”

James Longstreet was, indeed, “a soldier every inch,” which was why General Robert E. Lee made him his senior corps commander and regarded “Old Pete” as his “old war-horse.” Second only to Stonewall Jackson, he was Lee’s most trusted subordinate. But after the war, he also became the most controversial of the Confederate generals, with many Southerners blaming James Longstreet for the South’s defeat because of his conduct at Gettysburg.

A Dutchman Among Cavaliers

Born in South Carolina, though raised in Georgia (which he considered his true home state), and sent to West Point by Alabama, James Longstreet was, like most of the leading officers of the war, the product of an American lineage that went back to colonial times. He was the son of a small-scale planter, and grew up as a tall, vigorous youth—a man of few words (and not much book learning), but a hardy, rough, dependable, confident, and independent soul. He was also stubborn as a Dutchman, and it was Dutch blood that ran in his veins.

One of the most famous early twentieth century biographies of James Longstreet noted that “there was something curiously unSouthern about him. He was serious and stolid, not romantic as proper Southerners of that age were, more materialistic than idealistic.” He also, as it happened, was a great friend of U. S. Grant both at West Point and as young officers. James Longstreet in fact introduced Grant to one of his cousins, Julia Dent, whom Grant subsequently married. After the war, Longstreet and Grant not only renewed their friendship but became political allies, with Longstreet famously (or infamously) turning Republican politician during Reconstruction in Louisiana.

James Longstreet was the only non-Virginian of Robert E. Lee’s early corps commanders—Stonewall Jackson, A. P. Hill, Richard Ewell, and J. E. Stuart—a singularity that Longstreet noted with disapproval, thinking there was a prejudice in favor of Virginians. Longstreet had no lack of amour propre, and though Lee was too high-minded to notice it, Longstreet was a bit of a mulish lieutenant, forever thinking that he should be in charge. While Lee sometimes characterized Longstreet as slow—which he was, because he was a very careful soldier—he never recognized that part of that slowness was a repeated reluctance to follow Lee’s ideas when they disagreed with his own.

Though he had performed admirably as a combat soldier in the MexicanWar, he found that as a family man, for he married in 1848, he needed more pay than he could earn as a line officer. So he became a military accountant, a major in the paymaster department of the United States Army. Had the War not intervened, Longstreet would have lived out his life contentedly settling accounts and spending his free time as a bluff, vigorous outdoorsman.

After Fort Sumter was fired upon, James Longstreet made a simple calculation— and it was one not guided by narrow self-interest. While many of his brother officers urged him to stay loyal to the Union, he countered with the argument: “I asked him what course he would pursue if his State should pass ordinances of secession and call him to its defence. He confessed that he would obey the call.” Longstreet decided that he belonged to Alabama, the state that had not only sponsored his military education but from which he was the seniorWest Point graduate (and thus likely to attain a higher rank).

Before he departed Fort Fillmore, New Mexico, he was asked by a young officer how long he thought the war would last. Longstreet replied,“ At least three years, and if it holds for five you may begin to look for a dictator,” at which, as Longstreet relates in his autobiography, the lieutenant responded, “If we are to have a dictator, I hope that you may be that man.” Longstreet’s lack of comment seems a nod of assent.

From Manassas to Manassas

In the short term, Longstreet’s goal was not to be a dictator, and not even to be a line officer, it was to be a paymaster of the Confederate armies—but West Pointers were too valuable for that. James Longstreet had left the United States Army as a major, was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the Army of the Confederate States of America, and was promptly promoted to brigadier general. He was sent to the frontlines of Northern Virginia to serve under the command of General P. G. T. Beauregard, and saw action at First Manassas. Though the bulk of the fighting was away from him, his troops fought well at Blackburn’s Ford and withstood long Federal bombardment. Longstreet, who had drilled his men to a fine pitch (for that stage of the war), showed his usual calm courage and tactical acumen.

But he was infuriated when, at the end of the battle, with the bluecoats on the run, he was ordered to make no pursuit. Moxley Sorrel recounts that he “saw Longstreet in a fine rage. He dashed his hat furiously on the ground, stamped, and bitter words escaped him.” Those bitter words were recorded as: “Retreat! Hell, the Federal army has broken to pieces.” Longstreet was not alone in his assessment. Stonewall Jackson shared it, as did Edward Porter Alexander, a young staff officer who would become a brigadier general of artillery. Alexander noted that “in fact the battle was treated as over as soon as the Federals retreated across Bull Run. It should have been considered as just beginning.” As it was, Longstreet’s men cheered him—they recognized him as a sturdy, talented, professional soldier, scrupulous with the lives of his men, and fearless under fire.

Though Stonewall Jackson won fame from Manassas, Longstreet won the race for promotion, rising to major general. The autumn was spent in inactivity, but the winter was marked by personal tragedy when three of

James Longstreet’s young children, ages one, four, and six died of scarlet fever, and the previously convivial, if laconic, Longstreet became tighter-lipped and more devoted to his Episcopal faith, the church in which, later in the war, perhaps under Lee’s influence, he was confirmed.

In the spring and summer of 1862, Longstreet turned in creditable performances overall—enough to make Lee regard him as “the staff in my right hand.” Though a taciturn man, Longstreet was, at his best, an inspiring presence on the battlefield. As Lee’s senior corps commander, Longstreet was considered the best administrator among his top generals. Longstreet certainly agreed, and estimated himself fhighly as a strategist and tactician. He saw his duty as bringing his men to the right place at the right time; and if he disagreed with the commanding general on what was the right place and the right time, he tried to impose his will on him, often successfully.

James Longstreet had command presence. Not one for blustery words and speeches, Longstreet motivated his men to face danger and win by acting as though a battle were no more dangerous for a brave man than sitting on a porch and drinking iced tea. Or in the words of Moxley Sorrel, Longstreet was “that undismayed warrior. He was like a rock in steadiness when sometimes in battle the world seemed to be flying to pieces.”

Though he commanded with certainty, conviction, and a reassuring calm, he was, of course, not always right. At Malvern Hill, during the Seven Days’ battles in front of Richmond, Jackson counseled Lee to flank the entrenched Federal position. Longstreet, however, argued for a frontal assault and even joshed the dyspeptic General D. H. Hill who was full of dire warnings, “Don’t get scared, now that we have got him licked.” What makes his exchange particularly interesting is its contrast with Longstreet’s later playing the role of D. H. Hill to the aggressive Lee at Gettysburg. And as at Gettysburg (where Longstreet was late in his attempt to take Little Round Top) there are those who wonder why Longstreet did not take Malvern Hill himself, before that high ground was occupied by the Federals.

At Second Manassas, Longstreet turned in a characteristic performance, both in the way it frustrated Lee’s desire to get at the enemy but also rewarded him with victory. James Longstreet left Jackson’s men holding the Union front in desperate battle, while he thoroughly surveyed the ground and put his troops in order. His delaying of his attack, despite three direct orders from Lee and the obvious pressure on Jackson, in favor of an unhurried reconnaissance, was “surely a characteristic Longstreetian touch.” But just as Longstreetian was the crashing blow that landed when he finally did make his assault, giving the Confederates a tremendous victory.

At Sharpsburg, in the Maryland campaign, the Confederate army fought on the defensive—Longstreet’s sort of battle. It was an epic of courage and endurance, the bloodiest day of the war, and as one pair of historians put it, “There are few things finer than the stand of the Southerners at Sharpsburg. It ranks with Thermopylae.”

Longstreet’s mastery of military tactics, learned from experience, and calmly applied in the heat of combat showed themselves here. Moxley Sorrel wrote that Longstreet’s tactician’s “eyes were everywhere,” adding that his “conduct on this great day of battle was magnificent. He seemed everywhere along his extended lines, and his tenacity and deepsetre solution, his inmost courage, which appeared to swell with the growing peril to the army, undoubtedly stimulated troops to great action, and held them in place despite all weakness.”

Sharpsburg also highlighted James Longstreet’s mordant, soldierly humor. At one point in the battle, Longstreet called out to D. H. Hill, who was riding up a crest while he and Lee walked. “If you insist on riding up there and drawing the fire,” Longstreet said, “give us a little interval so that we may not be in the line of fire when they open up on you.” Longstreet pointed to a puff of cannon smoke and joked that Hill was its target. Unfortunately, he was right. The artillery shell plowed into the front legs of Hill’s horse, severing them. Hill was stuck, unable to dismount as his rearing, screeching horse stumbled, lurched, and rolled on its bloody stumps. Longstreet had stomach enough, as a leathery old trooper, to laugh and make fun of his colleague’s predicament.

In the same battle, one of Longstreet’s staff officers—John Fairfax, a wealthy, fierce-eyed Virginia aristocrat never to be separated from his Bible, his portable bathtub, his supply of whisky, or his horses—blurted to Longstreet: “General, General, my horse is killed! Saltron is shot; shot right in the back!”

Longstreet gave Fairfax a “queer look,” amidst this slaughter of men in the bloodiest day of the War and counseled, “Never mind, Major. You ought to be glad you are not shot in the back!”

Lee so valued Longstreet’s performance at the battle of Sharpsburg that he was promoted to lieutenant general—making him Lee’s senior corps commander (ahead of Stonewall Jackson and J. E. B. Stuart). At Fredericksburg in December 1862, James Longstreet’s men, behind the stonewall at Marye’s heights, spent all day mowing down the charging Federals, with Longstreet assuring Lee: “General, if you put every man now on the other side of the Potomac on that field to approach me over the same line, and give me plenty of ammunition, I will kill them all before they reach my line.” Union losses at the battle were more than 12,500 men. Longstreet’s casualties were only about 500 of the 5,300 Confederate casualties.

Through his cool presence on the battlefield, Longstreet was able to transmit his own stubborn streak to his troops, making them resolute defenders and, when circumstances called for it, unstoppable chargers. Longstreet’s greatest insight as a battlefield leader was that in every battle, somebody is bound to run, and if the troops “will only stand their ground long enough like men, the enemy will certainly run.” That insight made him tenacious—especially tenacious at digging in and holding ground as he did at Fredericksburg were he not only had the protection of the stonewall, but had set his troops to building defensive fieldworks.

For Old Pete the lesson of Fredericksburg and previous battles was obvious: for the Confederacy the advantage—indeed the necessity—was to fight on the tactical defensive. It was the only way the South could make up for its relative lack of manpower. Southern troops—and their officers—might be hot-blooded, but a strong defensive line was far more likely to deliver victory, in James Longstreet’s view, than gallant charges.

It wasn’t, then, just a lack of sentimentality about horses that separated Longstreet from the Virginians. As a leader and as a soldier, Longstreet was far removed from lightning bolt Stonewall Jackson, the impetuous A. P. Hill, or the swashbuckling J. E. B. Stuart. While Lee accepted the strength of his defensive position at Fredericksburg, he was not as tied to the tactical defensive as Longstreet was—and indeed, Lee and Jackson regretted they could not capitalize on the Federals’ defeat, given the nature of the ground, with an offensive counterstroke to destroy the Union army. At both Sharpsburg and Fredericksburg, Jackson and Lee accepted the necessity of a tactical defensive posture, but were always probing and hoping for a chance to shift to the attack, while Longstreet was content to repel and annihilate the attacking Federals.

James Longstreet analyzed the South’s disadvantages in manpower, money, and materiel as clearly as did Lee, Jackson, Stuart, and A. P. Hill. But Longstreet came up with a different solution from that of the Virginians. The Virginians sought audacious offensive maneuvers to shock, surprise, and crush the enemy as quickly as possible, hoping to stun the Federals into thinking the cost of the war was too great. Longstreet believed a more important goal was sparing the Confederacy casualties it couldn’t afford by adopting the comparative safety of the tactical defensive. But if the South could not afford a long war, it could not afford Longstreet’s strategy.

Whatever their differing opinions on strategy and tactics, Lee and Longstreet had a cordial and respectful relationship during the war. The British officer and observer Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle noted that “it is impossible to please Longstreet more than by praising Lee” and that Longstreet “is never far from General Lee, who relies very much on his judgment. By the soldiers he is invariably spoken of as ‘the best fighter in the whole army.’” But it is equally true that Longstreet wanted an independent command. He asked to be detached from Lee’s forces and sent to Kentucky. Lee dismissed that idea, but did accept detaching him as departmental commander of Southern Virginia and North Carolina to help guard the coastline and bring in supplies for the Army of Northern Virginia.

Though James Longstreet did eventually return with supplies, he was unable to bring his troops back in time to join Lee for the great battle at Chancellorsville, where Lee, with 60,000 men, bested 130,000 Federals. Writing in 1936, historians H. J. Eckenrode and Bryan Conrad commented, “In his extremity Lee had fully exercised his genius and audacity and had won the greatest victory in American history,”20 and unfortunately, Lee’s old war horse, dispatched to foraging rather than fighting (though he did lay siege to the Federals in Suffolk, Virginia), wasn’t there.

But with Jackson’s death, Lee relied more than ever on his senior corps commander, “the staff in my right hand.” In reorganizing his army, he created an additional corps. Lee retained Longstreet as commander of the First Corps and Stuart as his commander of cavalry. The Second Corps went to Richard Ewell who had exchanged a leg of flesh for a leg of wood at Groveton during the Second Manassas campaign. The newly created Third Corps went to A. P. Hill. Lee called Ewell “an honest brave soldier who has always done his duty well” and A. P. Hill as “the best soldier of his grade with me.” Both were West Pointers and professional soldiers, but neither had Longstreet’s accomplishments nor his stamina.

Ewell had always been high-strung and Hill had always been impetuous. But there were already signs that Hill’s health was faltering and that Ewell was not the fighter he once was. Ewell was brave, but also a champion eccentric, in an army with no shortage of these. Short, with a “bald and bomb-shaped head” and “bulging eyes” protruding “above a prominent nose” many thought he looked like a bird, “especially when he let his head droop toward one shoulder, as he often did, and uttered strange speeches in his shrill, twittering lisp.” He could also be “spectacularly profane.” If he was popular with his men, he certainly lacked the solidity of James Longstreet. No one would have called Ewell an old war horse. Instead, they called him “old baldy.”

Longstreet had no objection to Lee’s initial strategy of invading Pennsylvania, because he did not shy away from strategic offensives. In fact, he continually recommended an invasion of Kentucky in the western theatre. But once an offensive was launched, he preferred to switch back to the tactical defensive, entrenching and waiting for the enemy to attack. He was happy enough following Lee on daring campaigns—as long as he felt the army would eventually hunker down. As he exclaimed to Lee during the Maryland campaign, “General, I wish we could stand still and let the damned Yankees come to us.”

He wanted the damned Yankees to come against a strong Confederate line in Pennsylvania too, by putting Lee’s army between the Federal army and Washington. But once the two armies became entangled, virtually by accident, at Gettysburg, Lee felt compelled to beat the Federals where they were. For all the second-guessing of Longstreet, and later historians, Lee’s accepting of the need to attack the Federals was rational. He wanted to deliver a quick, crushing defeat to the Federal army when the Confederacy needed it most. Yes, he was outnumbered, and the odds were against him, but his army had triumphed over such odds before. Striking the Union center on the third day of battle at Gettysburg was certainly no more impracticable and certainly no less likely to deliver victory than what James Longstreet recommended: trying to disengage from a battle already started, maneuvering in enemy territory, and potentially risking the defeat of the entire army, whose lines of retreat could have been sundered. Had Lee been able to entrust Stonewall Jackson with responsibility for flanking the Union left on the second day of Gettysburg or leading Pickett’s charge on the Third Day, the battle might have had a very different outcome. Jackson’s lightning obedience was what Lee needed, not Longstreet’s endless delays and stubborn reluctance to obey his orders.

Fredericksburg, where behind the stone wall at Marye’s Heights his soldiers mowed down wave after wave of Union troops, was Longstreet’s model battle, but those circumstances could not be recreated in Pennsylvania.

James Longstreet’s caution—and his ego—occasionally caused him to stumble, as he did at Gettysburg, where his half-hearted execution of Lee’s plans guaranteed their failure. But once the charge was shattered, Longstreet, conscience stricken, in his own words, “rode back to the line of batteries, expecting an immediate counterstroke, the shot and shell ploughed up the ground around my horse, and an involuntary appeal went up that one of them would remove me from scenes of such awful responsibility.” Longstreet, the responsible soldier, was back in action.

“Longstreet is the man!” After Gettysburg, Longstreet was eager to try his own hand, out from under Lee’s shadow, in the western theatre of the war. At Chickamauga, his first great engagement, he met with success, filing his troops into the right position at the right time for maximum effect. Chickamauga made him a hero in the West, where good news had been scarce. General John Breckinridge led the chorus of praise, proclaiming, “Longstreet is the man, boys, Longstreet is the man.”

Cigar between his bearded lips, Longstreet was again an imperturbable figure in combat. One officer in Tennessee called Longstreet “the boldest and bravest looking man I ever saw. I don’t think he would dodge if a shell were to burst under his chin.”

When another officer ducked as a shell passed overhead, Longstreet smiled and remarked, “I see you salute them.”

“Yes, every time.”

“If there is a shell or a bullet over there destined for us,” Longstreet replied, “It will find us.”

But if James Longstreet was a hero at Chickamauga, his fall was precipitate. After Chickamauga, he performed poorly at Lookout Mountain, acting oddly disengaged from his duties and (understandably) chafing at the authority of his superior officer, General Braxton Bragg. He even joined in an attempt to get Bragg removed from command.

Bragg was one of the most difficult officers in the Confederate service, and so prone to contention that he reputedly even argued with himself. But he was also a favorite of Jefferson Davis, to whom Longstreet and

Bragg’s other subordinate generals appealed. Davis responded by coming to Tennessee. Gathering Bragg’s generals together in Bragg’s presence, he asked them, individually, to state their case against their commander. After all the generals, however reluctantly, had confessed their belief that Bragg was unfit to command, Davis reaffirmed his confidence in Bragg and returned to Richmond, leaving in his wake a commanding officer poisoned with personal animosity against every one of his subordinate generals.

Bragg, at Davis’s suggestion, detached Longstreet for a quasi-independent command. His assignment was to recapture East Tennessee from the occupying Federals. If this fulfilled Longstreet’s desire for autonomy, he soon wished he was back under Lee’s sheltering wing. Longstreet’s Knoxville campaign was a fiasco, plagued by delays, and ending in abysmal, costly failure and in ugly recriminations when he tried to pass off blame for the defeat to his former friend General Lafayette McLaws.

In a mere three months, Longstreet’s star fell so drastically that he went from being “Longstreet the man” to “Peter the slow.” One well-placed observer in Richmond, Mary Chestnut, whose husband served on Jefferson Davis’s military staff, wrote: “Detached from General Lee, what a horrible failure, what a slow old humbug is Longstreet.”

Even Longstreet might have been inclined to accept Mrs. Chestnut’s verdict. The fact was, he was an excellent corps commander for Lee, but he was not Lee’s rival, or even Jackson’s, when it came to independent operations.

But back under Lee’s command, Longstreet was brilliant at the battle of the Wilderness, where he lived up to the postwar praise of Confederate General John Bell Hood who paid Longstreet the ultimate fighter’s compliment when he said, “Of all men living, not excepting our incomparable Lee himself, I would rather follow James Longstreet in a forlorn hope or desperate encounter against heavy odds. He was our hardest hitter.”

James Longstreet was a hard hitter for many reasons. One was simple competence. Robert E. Lee considered Longstreet his most reliable corps commander. As such, Longstreet had more troops under his command than any other officer, and when he committed men to combat, it was with carefully positioned skill, the ground surveyed, the troops at full strength. As one Virginia soldier put it: “Like a fine lady at a party, Longstreet was often late in arrival at the ball. But he always made a sensation when he got in, with the grand old First Corps sweeping behind him as his train.”

At the Battle of the Wilderness, however, Longstreet was wounded by his own men while scouting ahead of his lines—shot through the neck and shoulder. With James Longstreet down, the planned Confederate counterstroke faltered and was cancelled. The Wilderness was still a Confederate victory, but the opportunity to make it an overwhelming one was lost.

James Longstreet survived his wounds (though he would never regain full use of his right arm), and after recuperating in Georgia, he rejoined Lee for the final defensive struggle. Fighting the kind of war he preferred he was sturdy and immovable against Federal assaults, remaining stubbornly devoted to the cause until the end. It was unshakable Longstreet who at Appomattox disdained Union General George Armstrong Custer’s demand that he surrender to General Phil Sheridan. “I am not the commander of this army,” Longstreet said, glaring, “and if I were, I would not surrender it to General Sheridan.” A little later, James Longstreet advised Lee, as Lee rode to meet Grant, “General, if he does not give us good terms, come back and let us fight it out.” For as long as the South fought, Longstreet was there.

James Longstreet the Scalawag

But after the war, he was swiftly traduced and regarded as a scalawag. As a soldier, James Longstreet was a cautious and clever tactician. As a politician and controversialist, he was not. The “old bull of the woods,” a nickname he earned at Chickamauga, became the old bull of the china shop.

It was not that James Longstreet accepted Reconstruction, counseled in favor of cooperation, and repudiated any ideas of rebellion against the Federal government’s authority—many leading Confederates did that. It was that Longstreet took the additional step of allying himself with the Republican Party that was in charge of the Reconstruction program. He even commanded mostly black police and militia units in defense of the Republican governor of Louisiana—after a contested election in which the Republican and Democrat claimed victory, though the Republican was recognized by the Grant administration as the legitimate winner—and fought a battle in the streets against the Democrats’ Crescent City White League, many of whom were Confederates.

James Longstreet believed that “Since the negro has been given the privilege of voting, it is all important that we should exercise such influence over that vote, as to prevent its being injurious to us, & we can only do that as

Republicans . . . .Congress requires reconstruction upon the Republican basis. If the whites won’t do this, the thing will be done by the blacks, and we shall be set aside, if not expatriated.”

For James Longstreet, it was a simple matter of pragmatism, but for other Southerners, joining the “Black Republicans” amounted to a betrayal. Still, he was not alone in taking this course. In Virginia, the “Grey Ghost,” John Singleton Mosby, joined the Republican Party for much the same reason that Longstreet did. Both men were friends of Ulysses Grant, whom James Longstreet endorsed for president, and won appointment to a variety of political posts.

But if becoming a Black Republican was shock enough, a further shock to Southern sensibilities came when James Longstreet entered the battle of the books over who was to blame for the South’s defeat. He had the reasonable excuse of needing to defend himself from Lee’s partisans who, after Lee’s death, blamed James Longstreet’s performance at Gettysburg for the loss of the war. But Longstreet’s ill-tempered counterattack did not become a man who had enjoyed such an enduring and cordial relationship with Lee, and who had a son, born during the bitter Tennessee winter of 1863, who bore the name Robert Lee Longstreet.

James Longstreet miscalculated how he should defend his reputation. The “old bull of the woods” simply charged a red cape. He had done the same when he became a Republican, judging that “we are a conquered people. Recognizing this fact, fairly and squarely, there is but one course left for wise men to pursue, and that is to accept the terms that are now offered by the conquerors.” He did not realize that the conquering party’s control would soon be replaced by the “solid” Democratic South.

James Longstreet outlived most of his colleagues, and despite the controversy that surrounded him he was an active and eager participant in Confederate veterans’ activities, memorial associations, and reunions. He did not moulder in retirement, but received jobs from every Republican administration, starting with Grant’s successor Rutherford B. Hayes, until his death at age eighty-two. He also tried his hand at farming, which he enjoyed; remarried (he was a widower), finding a bride forty-two years his junior (she lived until 1962); and became a Roman Catholic.

But however many civilian jobs James Longstreet held, he died like an old soldier, with his last words to his wife being, “Helen, we shall be happier in this post.”

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Confederate Brigadier General James Longstreet: (1821-1904)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 13, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/confederate-brigadier-general-james-longstreet-1821-1904>

More Citation Information.